Chinese Medicine views the organism as being managed by functions that span both the mind and the body. For instance the Large Intestine ‘energy’ is the activity of letting go of what you don’t need and, if the thing is toxic to you, actively pushing it out. It was named the Large Intestine function because that organ is a good metaphor for the action (the large intestine organ performs that function within the digestive process). But the function itself can be seen acting in our relationships, in our creation of comfortable boundaries and in our rejection of ideas that go against our values. So the body-mind activity given the name of the Large Intestine is much broader than the physical function. This type of activity that spans both mind and body is what the Chinese meant by Qi.

Traditionally, each function is related to and can be influenced through a ‘meridian’, a pathway through the body. However, Chinese medicine has no explanation for why a particular pathway is related to a specific type of Qi. My research into infant development produced a possible explanation, because each meridian traces the development of a particular movement in a young child. For instance, the Large Intestine meridian runs along a chain of extensor muscles in the arm which the baby first uses to push against the floor, effectively pushing the floor away. Bonnie Bainbridge Cohen thinks that this is also a metaphor for the separation from the mother and that the ability to rise up from the ground is the first stage of individuation.

Later on, the baby learns to say no to food that she doesn’t want, another marker on the journey to individuality. Typically, the movement of saying ‘No’ involves turning the head away in disgust and simultaneously pushing away the offered food. This movement uses muscles along the whole of the Large Intestine meridian.

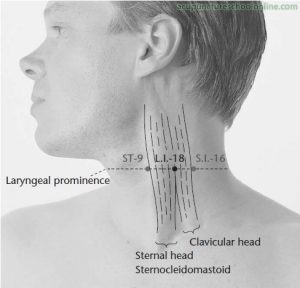

The muscle that turns the head away is the sternocleidomastoid muscle which contains the meridian. The end of the meridian is just under the nostril which smells the object of disgust and initiates the turning away.

This ability to say No is the complement of the ability to reach for and get what we need. This need-getting function is metaphorically related to and given the name of the Stomach. Both are necessary for physical health in the process reaching for our needs that and rejecting what is toxic. Both functions are equally necessary for creating healthy emotional boundaries – actively opening to relationships that are good for you and rejecting those that would damage you.

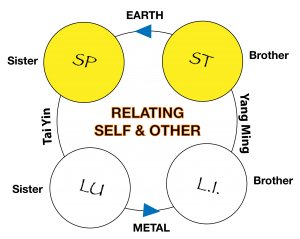

So the Stomach and Large Intestine form a pair of collaborating functions which maintain healthy boundaries. Both are necessary for this deeper function and the combination is traditionally one of the so called “Six Divisions”. However, the translation “Division” or “Layer” is derived from the Chinese model which names six degrees of severity in illness, while the pair of collaborating functions is an aspect of health. So I prefer now to call them the Six Wellbeing Functions. Each Wellbeing function is a collaboration of two meridian functions and embodies a deeper archetype than either of the meridians.

The ancient Chinese medical text, the Ling Shu, states “The arms reach to Heaven while the legs stand on the Earth”. So each arm meridian embodies an energy through which our body expresses mental and spiritual capacities. In contrast the leg meridians express the way in which our feelings, thoughts and spirit can become embodied, supported by the Earth and transformed into action. The combined channel forms a bridge between the body and spirit and this bridge is a kind of combination of the energies of the leg and arm meridian. Just as the Five Elements combine the meridians into Yin-Yang pairs, as if they were brother and sister, the divisions combine them into Yang-Yang and Yin-Yin pairs, two brothers and two sisters.

As we have seen, the Stomach and the Large Intestine together form one such combined function, called the Yang Ming, which means Bright Yang in Chinese. Both of the Stomach and Large Intestine functions are Yang, which means they are active and motor oriented. The Yang Ming actively mediates our exchange with the outer world and gives us our sense of self and other.

The Yin “sister” of the Stomach is the Spleen whose function is to receive the nourishment, filling and toning the flesh. The Yin sister to the Large Intestine is the Lung who is also elder sister of the Spleen. The Lung’s relationship to the Large Intestine is that she expands us to fill our personal space the boundaries of which the Large Intestine guards. This expansive energy is also protective and allows us to have clear boundaries without them becoming barriers to contact. The Lung’s relationship to the Spleen is that she continues the inner expansion of the Spleen into the outer world. Together the Spleen and the Lung combine into the Tai Yin Wellbeing Function, whose action is expansive and receptive. If our boundaries are clear we can be open to input, be nourished by it and expand out into the world, expressing our truth rather than contracting and defending. This is the characteristic of the Tai Yin.

Together the yang Ming and the Tai Yin make a family which has the profound but simple function of maintaining our positive sense of self, being grounded and having clear boundaries (which are the attributes of the Earth and Metal Elements in Chinese Medicine).

Each series of Inner Qigong traces the movements and activities of a similar cycle of four meridians, typically cycling from the earth into the physical body, then feeling how the physical action is also a mental / spiritual action which relates to our abstract self and then connecting the mental / spiritual aspect of ourselves to the ground.

Here are two videos, the first describes the four meridians in the first cycle and shows their function and how they develop through infant movements. The second takes you through the Inner Qigong form of the first cycle.

And another version: